Indeed, some creatures of the sea can seem more alien than anything you can imagine.

But even worse, some of them can seem more frightening than your worst nightmare.

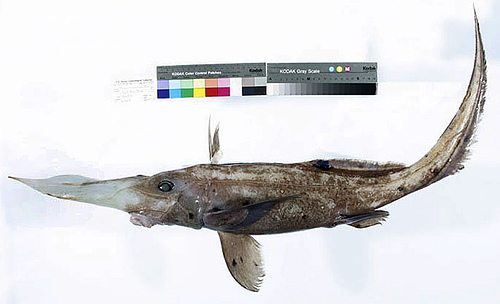

Chimaeras are cartilaginous fish related to the sharks and rays, and are sometimes called ghost sharks or rabbitfishes. For defense, most chimaeras have a venomous spine located in front of the dorsal fin.This strange cartilaginous fish uses its long snout to scan over the sea floor for the electrical impulses of its prey that bury in the muddy sea floor, just like a metal detector. Like other chimaeras (such as ghost and elephant sharks), these animals lay horny egg cases in which their young are left to develop, potentially for up to one year.

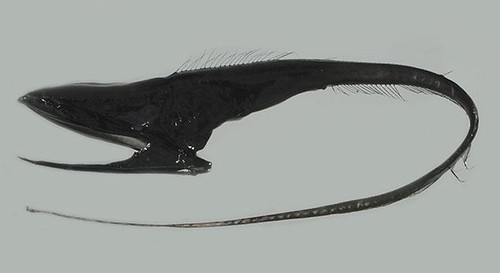

Pelican eel's most notable feature is its enormous mouth, much larger than its body. The mouth is loosely-hinged, and can be opened wide enough to swallow a fish much larger than the eel itself. The pouch-like lower jaw resembles that of a pelican, hence its name. The stomach can stretch and expand to accommodate large meals, although analysis of stomach contents suggests that the eels primarily eat small crustaceans. Despite the great size of the jaws, which occupy about a quarter of the animal's total length, it has only tiny teeth, which also would not be consistent with a regular diet of large fish.[1]

The eel uses a whip-like tail for movement. The end of the tail bears a complex organ with numerous tentacles, which glows pink and gives off occasional bright red flashes. This is presumably a lure to attract prey, although its presence at the far end of the body from the mouth suggests that the eel may have to adopt an unusual posture to use it effectively. Pelican eels are also unusual in that the lateral line organ projects from the body, rather than being contained in a narrow groove; this may increase its sensitivity.[1]

The pelican eel grows to about 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length and is found in all tropical and subtropical seas at depths ranging from 900 to 8,000 meters (3,000 to 26,200 feet).

The Colossal Squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, from Greek mesos (middle), nychus (claw), and teuthis (squid)), sometimes called the Antarctic or Giant Cranch Squid, is believed to be the largest squid species in terms of mass. It is the only known member of the genus Mesonychoteuthis. Though it is known from only a few specimens, current estimates put its maximum size at 12–14 metres (39–46 feet) long,[1] based on analysis of smaller and immature specimens, making it the largest known invertebrate.The squid's known range extends thousands of miles northward from Antarctica to southern South America, southern South Africa, and the southern tip of New Zealand, making it primarily an inhabitant of the entire circumantarctic Southern Ocean.

Ocean sunfish, Mola mola, or common mola, is the heaviest known bony fish in the world. It has an average adult weight of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb). The species is native to tropical and temperate waters around the globe. It resembles a fish head with a tail, and its main body is flattened laterally. Sunfish can be as tall as they are long when their dorsal and ventral fins are extended.The caudal fin of the ocean sunfish is replaced by a rounded clavus, creating the body's distinct truncated shape. The body is flattened laterally, giving it a long oval shape when seen head-on. The pectoral fins are small and fan-shaped, while the dorsal fin and the anal fin are lengthened, often making the fish as tall as it is long. Specimens up to 3.2 m (10.5 ft) in height have been recorded.[8]

The mature ocean sunfish has an average length of 1.8 m (5.9 ft), a fin-to-fin length of 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and an average weight of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb),[1] although individuals up to 3.3 m (10.8 ft) in length[8] 4.2 m (14 ft) across the fins[9] and weighing up to 2,300 kg (5,100 lb)[10] have been observed.

The spinal column of M. mola contains fewer vertebrae and is shorter in relation to the body than that of any other fish.[11] The spinal cord of a specimen measuring 2.1 m (6.9 ft) in length is under 25 mm (1 in) long.[12][citation needed] Although the sunfish descended from bony ancestors, its skeleton contains largely cartilaginous tissues, which are lighter than bone, allowing it to grow to sizes impractical for other bony fishes.

Stargazers are a family Uranoscopidae of perciform fish that have eyes on top of their heads (thus the name). The family includes about 50 species in 8 genera, all marine and found worldwide in shallow waters.

In addition to the top-mounted eyes, stargazers also have a large upward-facing mouth in a large head. Their usual habit is to bury themselves in sand, and leap upwards to ambush prey (benthic fish and invertebrates) that pass overhead. Some species have a worm-shaped lure growing out of the floor of the mouth, which they can wiggle to attract prey's attention. Both the dorsal and anal fins are relatively long; some lack dorsal spines. Lengths range from 18 cm up to 90 cm, for the giant stargazer Kathetostoma giganteum.

Stargazers are venomous; they have two large poison spines situated behind the opercle and above the pectoral fins. Some species can also cause electric shocks. They have an electric organ consisting of modified eye muscles. They are one of the few[1] marine bony fishes that are electrogenic. They are also unique among electric fish in not possessing specialized electroreceptors.

Grenadiers or rattails (less commonly whiptails) are generally large, brown to black gadiform marine fish of the family Macrouridae. Found at great depths from the Arctic to Antarctic, members of this family are among the most abundant of the deep-sea fishes.

The Macrouridae are a large and diverse family with some 34 genera and 383 species recognized (well over half of which are contained in just three genera, Caelorinchus, Coryphaenoides and Nezumia). They range in length from approximately 10 centimetres (3.9 in) in the graceful grenadier (Hymenocephalus gracilis) to 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in the giant grenadier, Albatrossia pectoralis. An important commercial fishery exists for the larger species, such as the giant grenadier and roundnose grenadier, Coryphaenoides rupestris. The family as a whole may represent up to 15 percent of the deep-sea fish population.

Typified by large heads with large mouths and eyes, grenadiers have slender bodies that taper greatly to a very thin caudal peduncle or tail (excluding one species, there is no tail fin): this rat-like tail explains the common name rattail and the family name Macrouridae, from the Greek makros meaning "great" and oura meaning "tail". The first dorsal fin is small, high and pointed (and may be spinous); the second dorsal fin runs along the rest of the back and merges with the tail and extensive anal fin. The scales are small.

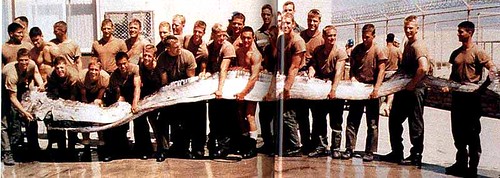

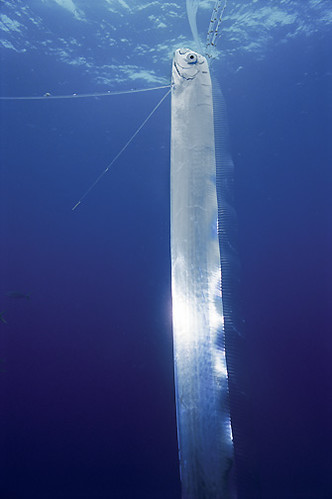

Oarfish are large, greatly elongated, pelagic Lampriform fishes comprising the small family Regalecidae.[1] Found in all temperate to tropical oceans yet rarely seen, the oarfish family contains four species in two genera. One of these, the king of herrings (Regalecus glesne), is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest bony fish alive, at up to 17 metres (56 ft) in length.[2][3]

The common name oarfish is presumably in reference to either their highly compressed and elongated bodies, or to the former (but now discredited) belief that the fish "row" themselves through the water with their pelvic fins.[4] The family name Regalecidae is derived from the Latin regalis, meaning "royal". The occasional beachings of oarfish after storms, and their habit of lingering at the surface when sick or dying, make oarfish a probable source of many sea serpent tales.

Although the larger species are considered game fish and are (to a minor extent) fished commercially, oarfish are rarely caught alive; their flesh is not well regarded due to its gelatinous consistency.

Megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios, is an extremely rare species of deepwater shark. Since its discovery in 1976, only a few megamouth sharks have been seen, with 53 specimens known to have been caught or sighted as of 2011, including three recordings on film. Like the basking shark and whale shark, it is a filter feeder, and swims with its enormous mouth wide open, filtering water for plankton and jellyfish. It is distinctive for its large head with rubbery lips. It is so unlike any other type of shark that it is classified in its own family Megachasmidae, though it has been suggested that it may belong in the family Cetorhinidae of which the basking shark is currently the sole member.Megamouths are very large sharks, able to grow to 5.5 metres (18 ft) in length. Males mature by 4 metres (13 ft) and females by 5 metres (16 ft). Weights of up to 1,215 kg (2,680 lb) have been reported.

As their name implies, megamouths have a large mouth with small teeth, and a broad, rounded snout, causing observers to occasionally mistake megamouth for a young orca. The mouth is surrounded by luminous photophores, which may act as a lure for plankton or small fish. Their mouths can reach up to 1.3 metres wide.

Fangtooths are beryciform fish of the family Anoplogastridae (sometimes spelled "Anoplogasteridae") that live in the deep sea. The name is from Greek anoplo meaning "unarmed" and gaster meaning "stomach". With a circumglobal distribution in tropical and cold-temperate waters, the family contains only two very similar species, in one genus, with no known close relatives: the common fangtooth, Anoplogaster cornuta, found worldwide; and the shorthorned fangtooth, Anoplogaster brachycera, found in the tropical waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean.The head is small with a large jaw and appears haggard, riddled with mucus cavities delineated by serrated edges and covered by a thin skin. The eyes are relatively small, set high on the head; the entire head is a dark brown to black and is strongly compressed laterally, deep anteriorly and progressively more slender towards the tail. The fins are small, simple, and spineless; the scales are embedded in the skin and take the form of thin plates. As compensation for reduced eyes, the lateral line is well-developed and appears as an open groove along the flanks.

In adults, the largest two fangs of the lower jaw are so long that the fangtooths have evolved a pair of opposing sockets on either side of the brain to accommodate the teeth when the mouth is closed. According to BBC's Blue Planet- The Deep -, the Fangtooth has the largest teeth of any fish in the ocean, proportionate to body size. The juveniles are morphologically quite different - unlike the adults, they possess long spines on the head and preoperculum, larger eyes, a functional gas bladder, long and slender gill rakers, much smaller and depressible teeth, and are a light gray in colour. These differences once caused the two life stages to be classed as distinct species, with one in another genus; Caulolepsis.

Sea robins, also known as gurnard, are bottom-feeding scorpaeniform fishes in the family Triglidae. They get their name from their large pectoral fins, which, when swimming, open and close like a bird's wings in flight.

They are bottom dwelling fish, living at depths of up to 200 m (660 ft). Most species are around 30 to 40 cm (12 to 16 in) in length. They have an unusually solid skull, and many species also possess armored plates on the body. Another distinctive feature is the presence of a "drumming muscle" that makes sounds by beating against the swim bladder.[1] When caught, they make a croaking noise similar to a frog.

Sea robins have six spiny "legs", three on each side. These legs are actually flexible spines that were once part of the pectoral fin. Over time, the spines separated themselves from the rest of the fin, developing into feeler-like "forelegs." The pelvic fins have been thought to let the fish "walk" on the bottom, but are really used to stir up food. The first three rays of the pectoral fins are membrane free and used for chemoreception.

Sea robins have sharp spines on their gill plates and dorsal fins that inject a mild poison, causing slight pain for two to three days.

The Sparkling Enope Squid is found in the Western Pacific ocean at depths of 183 to 366 metres (600 - 1200 feet) and exhibits bioluminescence. Each tentacle has an organ called a photophore, which produces light. When flashed, these lights attract small fish, which the squid can then feed upon. The Sparkling Enope Squid is the only species of cephalopod in which evidence of color vision has been found. While most cephalopods have only one visual pigment, firefly squid have three, along with a double-layered retina. These adaptations for color vision may have evolved to enable firefly squid to distinguish between ambient light and bioluminescence. The Sparkling Enope Squid measures about 3 inches long at maturity and dies after one year of life. It has the standard eight arms and two tentacles, with one pair each having three bright light-emitting organs at the tips.

It spends the day at depths of several hundred metres, returning to the surface when night falls. Light-sensing organs enable it to match its underside to the brightness and colour coming from the surface (countershading), making it hard for predators from below to detect it.

Handfish are anglerfish in the family Brachionichthyidae, a group which comprises five genera and fourteen extant species.

They are small (up to 15 cm) bottom-dwelling marine fish found in coastal waters of southern Australia and Tasmania. Their skin is covered with denticles (tooth-like scales), giving them the name warty anglers. This is the most species-rich of the few marine fish families that are endemic to Australia. Handfish are unusual, slow moving fishes that prefer to 'walk' rather than swim, using their modified pectoral fins to move about on the sea floor. These highly modified fins have the appearance of hands, hence their scientific name, from Latin bracchium meaning "arm" and Greek ichthys meaning "fish".

Like other anglerfish, they possess an illicium, a modified dorsal fin ray above the mouth, but it is short and does not appear to be used as a fishing lure.[dubious – discuss][1] The second dorsal spine is joined to the third by a flap of skin, making a crest.

histionotophorus bassani

The prehistoric species, Histiontophorus bassani, from the Lutetian of Monte Bolca, is now considered to be a handfish, sometimes even being included in the genus Brachionichthys.

Stomiidae is a family of deep-sea ray-finned fish, including the barbeled dragonfishes, stareaters and loosejaws.

Stomiids are generally elongated fish with black or near-black bodies, but they are highly variable in form, and are sometimes grouped into multiple different families as a result. The largest species are about 40 centimetres (16 in) in length, with most being about half that. Most species lack any scales, and have numerous small light-producing photophores scattered over their bodies. In some species, a larger photophore dangles from a barbel attached to the lower jaw, presumably as a lure to attract prey. Many species also have photophores attached to the pectoral fins, which are highly mobile, allowing the light to be moved about.[1]

They are predators, eating smaller fish, and have greatly enlarged, fang-like, teeth. Their gut is heavily pigmented, so that any luminescent organs in their prey cannot shine through their bodies and attract larger predators.[1]

Like many other deep-water fishes, stomiids produce buoyant eggs, that float up into the surface waters to hatch. The larvae live among the plankton close to the surface, and only swim down to the depths when they begin to take on adult form. Some species are known to be able to change from male to female as they age, increasing their chances of finding a mate.[1]

The Blue-ringed octopuses (genus Hapalochlaena) are three (or perhaps four) octopus species that live in tide pools in the Pacific Ocean, from Japan to Australia (mainly around southern New South Wales and South Australia[1]). They are currently recognized as one of the world's most venomous marine animals.[2] Despite their small size and relatively docile nature, they can prove a danger to humans. They can be recognized by their characteristic blue and black rings and yellowish skin. When the octopus is agitated, the brown patches darken dramatically, and iridescent blue rings or clumps of rings appear and pulsate within the maculae. Typically 50-60 blue rings cover the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the mantle. They hunt small crabs, hermit crabs, and shrimp, and may bite attackers, including humans, if provoked.

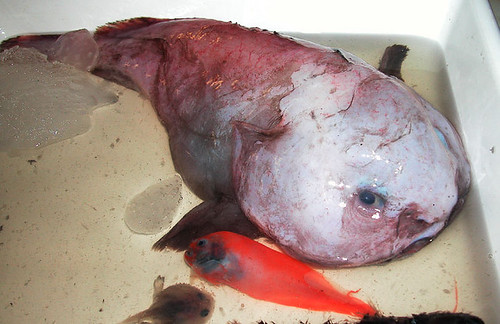

The blobfish (Psychrolutes marcidus) is a deep sea fish of the family Psychrolutidae. Inhabiting the deep waters off the coasts of mainland Australia and Tasmania,[1] it is rarely seen by humans.

Blobfish live at depths where the pressure is several dozen times higher than at sea level, which would likely make gas bladders inefficient for maintaining buoyancy. Instead, the flesh of the blobfish is primarily a gelatinous mass with a density slightly less than water; this allows the fish to float above the sea floor without expending energy on swimming. Its relative lack of muscle is not a disadvantage as it primarily swallows edible matter that floats in front of it.

Blobfish can be caught by bottom trawling with nets as bycatch. Such trawling in the waters off Australia may threaten the blobfish in what may be its only habitat.[2]

The Blobfish is currently facing extinction due to deep-sea fishing.

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea. They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. There are a number of holothurian /ˌhɒloʊˈθjʊəriən/ species and genera, many of which are targeted for human consumption. The harvested product is variously referred to as trepang, bêche-de-mer or balate.

Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have an endoskeleton just below the skin, calcified structures that are usually reduced to isolated microscopic ossicles (or sclerietes) joined by connective tissue. In some species these can sometimes be enlarged to flattened plates, forming an armour. In pelagic species such as Pelagothuria natatrix (Order Elasipodida, family Pelagothuriidae), the skeleton and a calcareous ring are absent.[1]Mariana Islands often encounter the local variation, called balate, which litters the sea floor all around the island, including in water as shallow as 3 feet (91 cm). These jet black sea cucumbers are normally 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long, 1.5 to 2.0 inches (3.8 to 5.1 cm) in diameter and are often curled up, partially covered with sand from the sea floor.

The most common way to separate the subclasses is by looking at their oral tentacles. Subclass Dendrochirotacea has 8-30 oral tentacles, subclass Aspidochirotacea has 10-30 leaflike or shieldlike oral tentacles, while subclass Apodacea may have up to 25 simple or pinnate oral tentacles and is also characterized by reduced or absent tube feet, as in the order Apodida.

The Lizardfishes (or typical lizardfishes to distinguish them from the Bathysauridae and Pseudotrichonotidae) are a family, the Synodontidae, of aulopiform fish. They are found in tropical and subtropical marine waters throughout the world.

Lizardfishes are generally small fish, although the largest species are about 60 centimetres (24 in) long. They have slender, somewhat cylindrical bodies, and heads that resemble those of lizards. The dorsal fin is located in the middle of the back, and accompanied by a small adipose fin placed closer to the tail.[2] They have mouths full of sharp teeth, even on the tongue.[1]

They are bottom-dwelling fish, living in shallow coastal waters; even the deepest dwelling lizardfish lives in waters no more than 400 metres (1,300 ft). Some species in the subfamily Harpadontinae even live in brackish estuaries. They prefer sandy environments, and typically have body colours that help to camouflage them in such environments.

The larvae of lizardfishes are free-swimming. They are distinguished by the presence of black blotches in their guts, clearly visible through their transparent, scale-less, skin.